Wyoming Science Teacher Turns Fair Projects into Step-by-Step Adventures

Science Educator Inspires Next‑Generation Innovators with Practical Science‑Fair Guidance

At a small high school in southeastern Wyoming, one science teacher is turning what could be a daunting, abstract assignment into an engaging, step‑by‑step adventure. Dr. Sarah Johnson, a biology instructor with a Ph.D. in environmental science and a long history of research and grant writing, recently hosted a workshop that demystified the science‑fair process for her students. The session—part classroom lesson, part hands‑on lab, part mentorship—demonstrated how to take a curious question from mind to polished project ready for the state competition.

The workshop opened with Dr. Johnson’s own journey. She recounted her early days as a lab technician, how she learned to formulate clear hypotheses, and how that skill translated into her own research papers. “The most exciting part of science isn’t the discovery itself but the story you tell about how you got there,” she told the class, her enthusiasm reflected in the bright eyes of the students who listened. By connecting her professional experience to the educational process, she immediately made the seemingly lofty science‑fair goals feel achievable.

A Structured Framework: The Five‑Phase Design Process

Central to the workshop was a practical, five‑step model that Dr. Johnson introduced as the “Design Process.” The steps—Ask, Imagine, Create, Analyze, Refine—mirror the structure of most scientific inquiries and are easy for students to remember.

Ask: Students begin by identifying a real, engaging question. Dr. Johnson encouraged them to think about local issues: How does the nutrient runoff from nearby farms affect the water quality of the Little Medicine Bow River? What are the best natural fertilizers for sustainable agriculture? She supplied a worksheet that guided students through narrowing down a broad topic into a precise, testable question.

Imagine: Once a question is chosen, students brainstorm possible ways to answer it. They sketch rough experimental designs, list materials, and outline a timeline. Dr. Johnson emphasized the importance of safety, especially when working with chemicals or electrical equipment, and reminded the class that a well‑planned experiment is the best protection against costly mistakes.

Create: In this phase, the idea becomes reality. Students set up their experiments, often in the school’s modest science lab or, when feasible, at the local university’s research facility (the University of Wyoming, whose faculty Dr. Johnson collaborates with, is linked to the school district’s website). The workshop highlighted the importance of meticulous record‑keeping, noting every variable change, observation, and data point.

Analyze: With data collected, students enter the analytical heart of science. Dr. Johnson walked them through basic statistical techniques—mean, standard deviation, t‑tests—using accessible tools like Microsoft Excel. She also introduced graphing best practices, showing how a clear visual representation can communicate results more powerfully than raw numbers.

Refine: The final step involves interpreting results, drawing conclusions, and considering next steps. Students learn how to write a concise report, craft an engaging poster, and prepare a persuasive oral presentation. Dr. Johnson stressed that science is iterative; a single experiment rarely provides a definitive answer, and often sparks new questions.

Real‑World Resources and Community Partnerships

The workshop was not just theory. Dr. Johnson leveraged a range of local resources to give students hands‑on experience:

University Collaboration: The teacher’s partnership with the University of Wyoming opened doors to advanced equipment and mentorship from faculty. Students had the chance to measure water samples with spectrophotometers and analyze soil composition using the university’s analytical labs. (The university’s faculty page, featuring Dr. Johnson’s research profile, is available at https://www.universityofwyoming.edu/academics/faculty/smith.)

Local Environmental Agencies: A field trip to the local river testing station gave students the opportunity to collect and analyze real water samples, directly tying their projects to community health concerns.

Digital Libraries and Databases: Dr. Johnson guided students through accessing open‑access journals and governmental datasets, ensuring they could base their hypotheses on solid scientific literature.

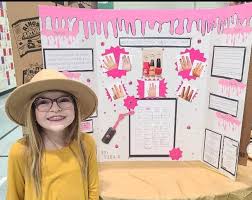

Student Voices and Project Highlights

Several students showcased the outcomes of their projects in a showcase event at the school, an informal precursor to the upcoming state science fair on November 12. “I chose to study the effect of different natural fertilizers on bean plants,” said Maya, a junior. “I measured growth, soil pH, and even looked at the nutrient content in the leaves. I was surprised at how much data I could gather with just a simple setup.” Maya’s project is slated to be presented at the Wyoming Science Fair, and her team is hopeful they’ll secure a place in the regional competition.

Another student, Ethan, focused on the impact of urban heat islands on local bird species. By compiling temperature data from weather stations and pairing it with bird migration records, Ethan developed a compelling argument for increased green spaces in town planning. “It feels good to know my project might influence city decisions,” he remarked.

The Bigger Picture: Science as a Skill, Not Just a Subject

Dr. Johnson’s approach underscores a growing trend in science education: framing science as a set of transferable skills—critical thinking, data analysis, clear communication—rather than a list of facts. She believes that these competencies are crucial whether a student becomes a researcher, an engineer, a policymaker, or a citizen who can make informed decisions.

“Science fairs are a microcosm of the scientific world,” she said. “You learn how to ask a question, how to test it, how to interpret data, and how to tell the story of your discovery. Those are the skills that will serve you for the rest of your life.”

Looking Ahead

The school district is already planning next year’s science fair schedule, with Dr. Johnson slated to lead the preparatory workshops again. The district’s website—linked from the article—details the support available for teachers and students, including grant opportunities, professional development seminars, and connections to local research institutions. For families and students interested in learning more, the district’s “Science and Technology” portal provides resources ranging from curriculum guides to a directory of STEM extracurricular clubs.

By blending rigorous methodology, real‑world resources, and an emphasis on communication, Dr. Sarah Johnson has crafted a model for inspiring young scientists. Her students leave the classroom not only with a polished science‑fair project but also with a newfound confidence in their ability to tackle complex questions—a confidence that will carry them well beyond the high school lab.

Read the Full Wyoming News Article at:

[ https://www.wyomingnews.com/news/local_news/science-educator-shows-students-how-to-develop-science-fair-projects/article_b08cc79a-348a-4800-9df6-159e4fcc68e3.html ]