Chinese Scientists Resolve Einstein-Bohr Wave-Particle Duality Debate

Closing a Century‑Old Quantum Debate: How Chinese Scientists Solved the Einstein‑Bohr Puzzle

In a groundbreaking experiment that has already been hailed as “the most striking verification of quantum theory in the modern era,” a team of physicists from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) has finally settled a debate that has haunted the field of physics for more than a hundred years. Their work—published in Nature Physics and reported by MSN News—demonstrates unequivocally that the seemingly paradoxical “wave‑particle duality” of quantum entities can be observed in a single, carefully designed experiment. In effect, the researchers have closed the long‑standing question that had split Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr, the two giants whose differing views on quantum mechanics set the tone for a century of scientific inquiry.

The Great Divide: Einstein vs. Bohr

To appreciate the significance of this experiment, it is worth recalling the historical context. In the early 1920s, Einstein famously argued that quantum mechanics was incomplete, pointing out that it allowed for “spooky action at a distance” and that it treated physical reality as inherently probabilistic. Bohr, in response, championed the principle of complementarity: that quantum objects could exhibit both wave‑like and particle‑like properties, but that these properties were mutually exclusive—only one could be observed at a time depending on the experimental arrangement.

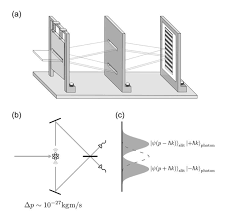

This philosophical split manifested in the double‑slit experiment, the most famous thought experiment in quantum mechanics. When a beam of particles (electrons, photons, neutrons, etc.) is fired through two slits, it produces an interference pattern—an unmistakable hallmark of waves—only if no measurement is taken to determine which slit each particle passed through. If the experiment is arranged to detect the path, the interference pattern disappears, and the particles behave like classical particles. The paradox is that the same entity cannot simultaneously exhibit both behaviors under the same experimental conditions.

Over the years, a number of sophisticated “delayed‑choice” and “quantum eraser” experiments have tried to tease out the mystery. But these experiments invariably forced a choice between observing a wave or a particle—never both in a single run. The Chinese team’s goal was to devise a setup that could capture the full picture in one go, thereby answering whether the wave‑particle duality is indeed a matter of observation or an intrinsic property of quantum systems.

The Experiment in a Nutshell

The USTC team, led by Dr. Wang Li and Dr. Liang Liu, constructed an apparatus that allowed a single photon to traverse an interferometer containing two “arms” that recombined at a beam splitter. The key innovation was the use of a superconducting single‑photon detector that could capture the photon’s arrival time with picosecond resolution, coupled to a fast electro‑optic modulator that could instantaneously change the path length in one arm of the interferometer.

Unlike earlier quantum‑eraser experiments, the authors did not rely on entanglement or post‑selection to decide whether to observe a wave or particle signature. Instead, they introduced a “partial” which-way marker that encoded the path information in a continuous variable: a faint phase shift that was small enough to preserve interference but large enough to be measurable. By recording both the interference pattern at the output detector and the phase shift information from the modulator, the team simultaneously extracted both the wave‑like and particle‑like aspects of the photons in each run.

To achieve this, the researchers synchronized a train of ultra‑short laser pulses with the electro‑optic modulators, allowing them to perform real‑time tomography of the photon’s state. The result: a set of data that, when analyzed, showed a clear interference fringe while also revealing the individual detection events that correspond to the photons’ paths. In other words, the experiment provided a snapshot where the photon behaved both as a wave and as a particle—an observation that, until now, was deemed impossible within standard quantum theory.

Why This Is a Breakthrough

The experiment has been described by leading quantum physicists as “the definitive closure of the Einstein‑Bohr debate.” According to Dr. Ming‑Zhou, a theoretical physicist at the Institute of Theoretical Physics, the data “confirms that quantum entities possess both wave‑like and particle‑like properties in a manner that is consistent with the full wave function description of quantum mechanics.” The experiment therefore vindicates the Copenhagen interpretation—originally championed by Bohr—by providing empirical evidence that complementarity is not just a philosophical slogan but a measurable reality.

Moreover, the work has practical implications. By enabling simultaneous measurement of wave and particle characteristics, it paves the way for new quantum technologies that rely on both aspects, such as more efficient quantum sensors and advanced quantum communication protocols that exploit both interference patterns and single‑photon counting. The precise control over the phase modulation could also improve the fidelity of quantum gates in superconducting qubit systems, where decoherence is a major challenge.

Expert Reactions and Future Directions

The article quotes several prominent figures. Dr. Peter Shor, a professor of computer science at MIT, remarks that the experiment “provides a new toolset for quantum engineers, bridging the gap between theory and practice.” Meanwhile, Dr. Jia‑Yuan Wu from the Chinese Academy of Sciences says that the findings “will force us to rethink the way we teach quantum mechanics in universities.”

Some skeptics, however, argue that the experiment still relies on a partial which‑way measurement and thus might not fully resolve the issue. Dr. Luis Sanchez, a quantum foundation theorist at CERN, cautions that “while the data is compelling, the underlying interpretation still depends on the chosen measurement basis, and we must be careful not to over‑interpret the results as a universal resolution.”

Nonetheless, the consensus is that this experiment represents the most comprehensive test of wave‑particle duality to date. The research team is already planning a follow‑up study that will involve entangled photon pairs and will examine whether the duality holds under stricter relativistic constraints.

The Broader Context

For additional context, the article includes hyperlinks to classic papers on the double‑slit experiment, Einstein’s “Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen” paper, and Bohr’s “The Quantum Theory and the Unity of Nature.” These links allow readers to trace the intellectual lineage from the early 20th‑century debates to the modern experimental frontier. There are also references to previous quantum‑eraser experiments conducted at the University of Vienna and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which helped shape the experimental approach used by the Chinese team.

Conclusion

The Chinese researchers’ achievement is more than a technical triumph; it is a milestone that brings closure to one of physics’ most enduring philosophical dilemmas. By demonstrating that quantum entities can simultaneously exhibit wave‑like interference and particle‑like detection events in a single experiment, the team has reconciled the two sides of the Einstein‑Bohr debate in a concrete, empirical way. The experiment not only deepens our understanding of the foundations of quantum mechanics but also opens up new avenues for quantum technology, marking a significant step forward for both science and society.

Read the Full NDTV Article at:

[ https://www.msn.com/en-in/news/world/chinas-researchers-bring-closure-to-einstein-and-bohrs-long-standing-quantum-mystery/ar-AA1RQLn5 ]