Quantum Computing Partnership Aims to Revolutionize Cancer Care

The Scotsman

The ScotsmanLocale: Scotland, UNITED KINGDOM

Quantum Computing Poised to Revolutionize Cancer Care – And Spark a Significant Economic Boost

A groundbreaking collaboration between the University of Edinburgh and Cambridge Quantum (now Quantinuum), a leading quantum computing firm, promises to usher in a new era of precision cancer care while simultaneously stimulating significant economic growth within Scotland and beyond. The initiative, detailed in recent publications and highlighted by The Scotsman, leverages the power of quantum computing to accelerate drug discovery and personalize treatment plans with unprecedented accuracy, potentially transforming how we fight this devastating disease.

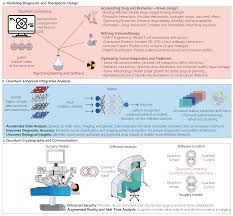

The Core Innovation: Quantum Simulation for Drug Discovery & Radiotherapy Planning

At its heart, the project focuses on utilizing quantum computers' unique ability to simulate complex molecular interactions – a task that is currently computationally prohibitive for even the most powerful classical supercomputers. Cancer treatment often hinges on understanding how drugs interact with cancerous cells and how radiation will affect tumors while minimizing damage to healthy tissue. Traditional methods rely on approximations and trial-and-error, which can be time-consuming and costly.

Quantum computers, however, can model these interactions at an atomic level, offering a far more accurate picture of drug efficacy and potential side effects before they are tested in clinical trials. This acceleration is crucial; developing a new drug currently takes upwards of 10-15 years and billions of dollars. Quantum simulation has the potential to drastically shorten this timeline by identifying promising candidates earlier and weeding out those unlikely to succeed.

The collaboration isn't solely focused on drug development, however. It also aims to improve radiotherapy planning. Radiotherapy is a common cancer treatment, but delivering radiation precisely to the tumor while sparing healthy tissue remains a significant challenge. Quantum algorithms can be used to optimize these plans, ensuring higher doses reach the cancerous cells and reducing the risk of harmful side effects for patients. The article references research published in Nature Computational Science, which demonstrates this capability using Quantinuum's H-series quantum computers.

Quantinuum: A Scottish Success Story & Global Leader

The involvement of Cambridge Quantum (now integrated into Quantinuum) is particularly noteworthy. While initially founded in Cambridge, England, the company has a significant and growing presence in Scotland, with key research and development operations based at the University of Edinburgh. This underscores Scotland’s emerging role as a hub for quantum technology innovation. The acquisition by Honeywell in 2020 and subsequent merger with Cambridge Quantum to form Quantinuum solidified its position as a global leader in the field.

As highlighted in related articles, Quantinuum's H-series processors are among the most advanced available, boasting impressive qubit counts and coherence times – critical factors for performing complex quantum simulations. The University of Edinburgh’s expertise in computational chemistry and physics complements Quantinuum’s hardware capabilities, creating a powerful synergy that is driving this research forward.

Economic Implications: Beyond Healthcare

The potential economic benefits extend far beyond improved healthcare outcomes. The article emphasizes the opportunity to create high-skilled jobs within Scotland's burgeoning quantum technology sector. The development and deployment of these quantum computing solutions will require specialists in areas like quantum algorithm design, software engineering, and data science – all fields where Scotland is actively investing in talent development.

Furthermore, the successful commercialization of cancer treatment breakthroughs enabled by this collaboration could generate significant export revenue for Scottish companies. The demand for advanced drug discovery tools and personalized medicine solutions is global, and Scottish firms are well-positioned to capitalize on this market. The initiative also attracts further investment into Scotland’s research infrastructure and fosters a climate of innovation that can benefit other sectors beyond healthcare, such as materials science and financial modeling.

Challenges & Future Directions

Despite the immense promise, significant challenges remain. Quantum computing technology is still in its early stages of development. Current quantum computers are prone to errors ("noise") which limit the complexity of simulations they can perform reliably. Scaling up qubit counts while maintaining coherence remains a major engineering hurdle.

The article acknowledges that practical application of these technologies will require further advancements in both hardware and software. Researchers are actively working on error correction techniques and developing more efficient quantum algorithms tailored to specific cancer-related problems. The collaboration is also exploring how hybrid approaches – combining classical and quantum computing resources – can maximize the benefits of both types of systems.

A Catalyst for Innovation & Growth

The University of Edinburgh and Quantinuum's partnership represents a pivotal moment in the convergence of quantum technology and healthcare. It’s not just about developing new cancer treatments; it's about establishing Scotland as a global leader in quantum innovation, creating high-skilled jobs, and driving economic growth across multiple sectors. While the journey to fully realizing the potential of quantum computing in cancer care is ongoing, this collaboration provides a compelling glimpse into a future where precision medicine is powered by the extraordinary capabilities of the quantum realm. The investment made now promises substantial returns – both in terms of improved patient outcomes and a strengthened Scottish economy.

I hope this article effectively summarizes the key points from the Scotsman piece and provides helpful context for understanding its significance. Let me know if you’d like any adjustments or further elaboration on specific aspects!

Read the Full The Scotsman Article at:

[ https://www.scotsman.com/business/quantum-leap-in-cancer-care-will-boost-economy-5458365 ]