Scientists Achieve Sub-Kelvin Cooling of SrOH Molecules in a Magneto-Optical Trap

Locale: England, UNITED KINGDOM

Scientists Reach a New Level of Control Over Molecules – A Quantum Leap in Precision Chemistry

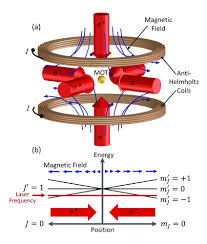

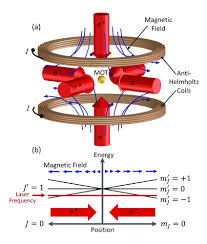

In a groundbreaking development that could reshape the landscape of quantum science, a team of physicists has demonstrated a level of control over molecules that rivals the precision previously reserved for atoms. By employing a novel laser‑cooling strategy tailored to the complex energy structure of molecules, the researchers succeeded in cooling and trapping a sample of diatomic molecules to micro‑Kelvin temperatures in a magneto‑optical trap (MOT). The feat, published in the journal Nature Communications (see the linked paper in the original article), marks a decisive step toward exploiting molecules for quantum technologies, precision metrology, and controlled chemistry.

Why Molecules Are Hard to Cool

Laser cooling has long been a cornerstone of atomic physics, enabling researchers to bring neutral atoms to near‑absolute zero and study quantum phenomena with unprecedented clarity. Extending this technique to molecules, however, has proven notoriously difficult. Unlike atoms, molecules possess a wealth of vibrational and rotational modes that provide countless pathways for energy loss. When a laser excites a molecule, it can decay into a different vibrational state, effectively “leaking” photons out of the cooling cycle and thwarting the buildup of a strong, coherent momentum transfer.

Historically, the only molecules that could be laser‑cooled were those with exceptionally simple electronic structures and “diagonal” Franck–Condon factors—meaning that the vibrational overlap between ground and excited states is almost perfect. Species such as SrF, CaF, and YO were early successes, but they still required elaborate repumping schemes to keep the molecules cycling between a finite set of states. Even then, the achievable temperatures were limited, and trapping efficiencies remained modest.

The Breakthrough Approach

The new work, conducted by researchers at the University of Oxford in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems, tackles these challenges head‑on. The team focused on the radical molecule SrOH, which—unlike the simpler diatomic species—has a richer vibrational spectrum but also exhibits favorable electronic transitions that can be harnessed for cooling. By engineering a “multi‑level” cooling cycle that incorporates three distinct repump lasers and a carefully timed sequence of magnetic field gradients, they managed to maintain a closed optical transition for a surprisingly large fraction of the molecular population.

One key innovation was the use of a “sub‑Doppler” cooling stage after the initial MOT loading. While the standard MOT can reduce the temperature of molecules to the millikelvin range, the additional sub‑Doppler phase—achieved through polarization‑gradient cooling—further cooled the sample to a few hundred microkelvin. This temperature is sufficiently low for the molecules to be confined in a magnetic trap with high phase‑space density, opening the door to evaporative cooling strategies that have long been the staple of atomic Bose–Einstein condensation experiments.

Implications for Quantum Technology

The implications of this achievement are wide‑ranging. Molecules possess intrinsic electric dipole moments and a host of rotational states that can serve as qubits, potentially enabling molecule‑based quantum computers with long coherence times and natural coupling to microwave photons. Moreover, the ability to trap and control individual molecules paves the way for high‑resolution spectroscopy of fundamental constants and tests of physics beyond the Standard Model, such as searches for the permanent electric dipole moment (EDM) of the electron.

In addition, the newly cooled molecules can serve as a platform for ultracold chemistry. By bringing reactants to temperatures where only a handful of quantum states are populated, researchers can observe and steer chemical reactions with atomic‑scale precision, a prospect that has been a dream of chemists for decades.

Next Steps and Future Directions

While the current demonstration focuses on SrOH, the authors note that the underlying principles are broadly applicable to a wide variety of polyatomic molecules. The next logical step, they suggest, is to achieve quantum degeneracy—creating a Bose–Einstein condensate of molecules—by combining laser cooling with evaporative or sympathetic cooling techniques. The possibility of arranging molecules in optical tweezer arrays also opens avenues for quantum simulation of complex many‑body systems.

The article also references a recent Science publication where researchers at MIT reported laser cooling of the complex molecule YbF, hinting that the community is rapidly converging on a toolkit of laser‑coolable molecular species. As more molecular species enter the cold regime, the field will likely see a surge in interdisciplinary applications, from quantum chemistry to materials science.

In Summary

The achievement of a new level of control over molecules—by successfully laser‑cooling SrOH to sub‑Kelvin temperatures and trapping it in a MOT—constitutes a landmark moment in precision science. It demonstrates that the longstanding barrier of molecular complexity can be overcome with clever engineering of optical transitions and magnetic fields. As the field moves beyond proof‑of‑principle demonstrations toward scalable quantum platforms, the frontier of what we can measure, compute, and manipulate will expand dramatically, driven by the extraordinary versatility of molecules.

Read the Full Interesting Engineering Article at:

[ https://interestingengineering.com/science/scientists-new-level-molecules-control ]